1. Introduction

In embedded systems, memory organization can be well described by the well-known proverb: "A place for everything, and everything in its place". Each program element must have a well-defined location in memory and, in the case of variables, the choice between static or dynamic allocation depends directly on the application context and the system objectives established during the design phase.

Although dynamic memory allocation is widely used in general-purpose systems, it is recognized that this mechanism introduces a series of problems when applied to systems that impose strict determinism requirements. In deterministic systems, it is expected that, for the same sequence of inputs and initial conditions, the software always produces the same sequence of internal states and observable outputs, while respecting known temporal bounds.

Classical literature on memory management points out that traditional dynamic allocation violates these principles by introducing execution-history-dependent behaviors, affecting both temporal predictability and memory usage. These effects are particularly critical in systems that use RTOS (Real-Time Operating Systems), where the ability to predict behavior during the design phase is a fundamental requirement.

In this article, widely documented side effects associated with the use of dynamic memory allocation in real-time environments are analyzed and demonstrated in practice on real hardware. These effects are observed through simple and controlled experiments, conducted with the FreeRTOS operating system running on an ARM Cortex-R5F microcontroller (TI AM243x), using direct inspection of memory and heap metadata via debugging.

2. A bit of theory

Dynamic allocation is suitable for general-purpose systems, in which software failures normally do not result in severe consequences. This includes desktops and more complex embedded systems that provide an MMU and execute an operating system. In such systems, errors related to heap usage tend to be detected and confined by the operating system, through mechanisms such as process memory isolation and invalid access handling, preventing a failure from compromising the entire system.

In these environments, this memory allocation strategy is used to handle unpredictable runtime workloads, resulting from the wide range of possible operations in general-purpose systems, such as variable-sized data structures and the presence of multiple concurrent processes. In contrast, static allocation is the dominant approach in deterministic and safety-critical embedded systems, such as DAL-A software (DO-178C), where predictability is a fundamental requirement and all possible runtime behavior must be known, analyzed, and controlled during the design phase, leaving no room for surprises during execution.

An important point to highlight in programs written in C is the destination of data in memory.

Statically allocated objects, such as global variables or variables declared with

static, have their allocation directed by the linker to fixed memory

regions, typically in the .data section (when initialized with non-zero values)

or .bss (when uninitialized or initialized to zero), having addresses determined

at design time and a lifetime equivalent to the entire execution of the software.

Automatic or local variables, in turn, are allocated on the stack, with implicit

creation and destruction associated with function entry and exit, offering temporal

predictability but limited space.

Dynamically allocated data resides on the heap, a memory region managed at runtime

by the libc allocator (for example, through malloc()), whose content and

organization evolve according to the history of allocations and deallocations.

Unlike static regions and the stack, the heap has no fixed layout nor implicit

object lifetime, requiring explicit deallocation by the program and introducing

temporal variability, fragmentation, and dependence on the global system state, characteristics

that make its behavior inherently less predictable compared to other memory regions.

2.1 Allocation examples

Static memory allocation

#define BUFFER_SIZE 128

static int buffer[BUFFER_SIZE];

void process(void)

{

buffer[0] = 42;

}

-

Through

#define BUFFER_SIZE 128, a constant known at compile time is defined, allowing the compiler and the linker to calculate in advance the exact amount of memory required to store the array. -

In the declaration

static int buffer[BUFFER_SIZE];, the arraybufferis statically allocated, having static storage duration and occupying a fixed memory region. Depending on its initialization, this variable will be placed by the linker in the.bsssection (if not initialized) or.datasection (if initialized), as defined in the system linker script. -

As a consequence of this static allocation, the address of

bufferis resolved at link time and remains unchanged throughout the entire execution of the program, with no calls to dynamic allocation functions and no dependence on the state of the heap. -

The access performed in

buffer[0] = 42;corresponds to a direct write to a valid and previously reserved memory address, not being subject to runtime failures, pointer checks, or variations resulting from the execution history of the system. - This memory usage model allows total RAM consumption and the execution time associated with accessing the array to be completely known and analyzed during the design phase, enabling formal analyses of memory usage and Worst-Case Execution Time (WCET), a fundamental requirement in deterministic and safety-critical systems.

Dynamic memory allocation

#include <stdlib.h>

void process(void)

{

int *buffer =

(int *)malloc(

128 * sizeof(int)

);

if (buffer != NULL)

{

buffer[0] = 42;

free(buffer);

}

}

-

The inclusion of

#include <stdlib.h>makes the standard dynamic allocation interface available, in particular themalloc()function, whose implementation depends on the runtime, operating system, or RTOS used. -

The expression

malloc(128 * sizeof(int))requests memory at runtime, dynamically calculating the number of bytes to be allocated. Unlike static allocation, the block size and the allocation moment are defined only during program execution. -

The call to

malloc()queries the internal state of the heap, searching for a free block large enough to satisfy the request, which implies direct dependence on the history of previous allocations and deallocations. -

The check

if (buffer != NULL)is necessary because dynamic allocation may fail at runtime, even when the total amount of free memory is theoretically sufficient, for example due to external heap fragmentation. -

The access performed in

buffer[0] = 42;is only safe after confirmation that allocation succeeded, highlighting that memory usage depends on additional checks and conditional paths in the execution flow. -

The call to

free(buffer)returns the memory block to the heap, modifying the internal state of the allocator and influencing future memory requests, reinforcing the dependence of system behavior on execution history. - As a consequence, both memory consumption and the execution time associated with allocation and deallocation operations are not fully predictable during the design phase, complicating formal analyses of memory usage and Worst-Case Execution Time (WCET), which makes this model more suitable for general-purpose systems than for deterministic or safety-critical systems.

2.2 malloc() and free()

It is important to mention that the C language does not have a specific storage class for dynamic memory allocation as it does with auto, static or extern. Dynamic allocation is not a property of the language's variables, being performed through allocators, functions such as malloc(), provided by the C standard library (libc).

This function manages a heap region provided by the execution environment. In systems with a full operating system, such as Linux-based environments, a call to malloc() is initially handled by the libc allocator in user space, which consults its internal structures to find a suitable free block. If the available heap is insufficient, the allocator resorts to low-level system calls, such as sbrk() or mmap(), to request the kernel to create or expand virtual memory regions associated with the process. From these regions, libc organizes and manages the application's heap and, finally, returns a pointer to the application for a valid virtual address, corresponding to a memory block reserved for use at runtime. Thus, the use of malloc() presupposes the existence of an operating system and a kernel capable of providing these services.

In embedded systems that do not have these low-level interfaces — such as bare-metal systems — dynamic allocation does not exist by default. In these cases, for malloc() to work, it is necessary to manually implement the so-called allocation hooks, or even a custom memory manager, usually based on heap regions defined in the linker script. Even in embedded systems that use an RTOS, the presence of these system calls is not guaranteed. In these environments, when dynamic allocation is supported, it usually operates over a heap region statically defined at design time, reinforcing its limited and runtime-dependent nature.

The heap is organized internally as a dynamic structure based on a linked list of free memory regions. Each free region contains control information stored in its own metadata, including the total block size and a reference to the next adjacent free region in terms of addressing. When an allocation request is made, the allocator traverses this list from the beginning of the heap until it finds a free block of sufficient size. If the selected block is larger than necessary, it is split into two parts: one portion is marked as allocated and delivered to the application, while the remaining portion remains free and is reinserted into the linked list as a new element. As allocations and deallocations occur, the list of free regions evolves continuously and may contain multiple non-contiguous blocks, which highlights the dynamic nature of the heap and its direct dependence on the history of memory usage throughout the system's execution.

Heap metadata are internal structures maintained by the allocator to describe the size, state, and relationship between dynamic memory blocks. These pieces of information are constantly updated during calls to malloc() and free(), allowing operations such as block splitting and merging. In practice, a request such as malloc(128) does not correspond to the exact occupation of 128 bytes in the heap. The allocator needs to reserve a larger block, capable of also storing its internal metadata and meeting the architecture's alignment requirements. Conceptually, the effective layout of an allocated block can be represented as follows:

[ allocator metadata ][ 128 requested bytes ][ padding / alignment ]

Thus, the allocator does not look for a free block of exactly 128 bytes, but rather a contiguous block large enough to accommodate this entire structure. As a consequence, even if there are 128 free bytes in the heap, the allocation may fail if there is no contiguous block that accommodates the necessary metadata and alignment, highlighting both internal fragmentation — caused by additional space unusable by the application — and external fragmentation, resulting from the dispersion of free blocks in the heap. This mechanism introduces memory overhead, dependence on execution history, and temporal variability in the allocator's behavior.

After dynamic allocation, it is necessary to return a previously obtained block via malloc() to the allocator, allowing this region to be marked as free again so it can be reused in future allocations. Without this explicit release, the block remains permanently occupied, progressively reducing the available space in the heap and potentially leading to allocation failures in long-running systems. In embedded and real-time environments, where the heap is limited and there is no automatic memory recovery, the omission of free() inevitably results in memory leaks and degradation of system behavior.

Problems of dynamic allocation in deterministic systems

Problems of dynamic memory allocation in deterministic systems

In deterministic systems, software behavior is expected to be completely predictable, both in temporal and spatial terms, allowing all relevant scenarios to be analyzed during the design phase. Dynamic memory allocation directly conflicts with this principle, as it introduces decisions and states that can only be resolved at runtime.

Unlike static allocation, in which the memory layout is fixed and known,

the use of malloc() depends on the global state of the heap

at the moment of the call. This state is the result of the history of

previous allocations and deallocations, making it impossible to guarantee

that two executions of the same code, under the same functional inputs,

will exhibit identical behavior in terms of memory usage and execution time.

In addition, the temporal cost of allocation and deallocation operations is not constant. The allocator may need to traverse internal structures, split or merge blocks and, in some cases, request new memory regions from the execution environment. This variability makes it impossible to reliably determine the Worst-Case Execution Time (WCET), an essential requirement in deterministic and safety-critical real-time systems.

Both internal and external fragmentation may also occur in the heap. Internal fragmentation occurs when the allocator needs to reserve a block larger than the size effectively requested by the application, either due to alignment requirements or minimum allocation granularity, causing part of the memory within the allocated block to remain unused. External fragmentation, on the other hand, manifests when free memory is distributed across multiple non-contiguous blocks interleaved between occupied regions, preventing new allocations that require a contiguous block of a given size. In this situation, even when the total amount of free memory is sufficient, the absence of suitable contiguous regions may lead to runtime allocation failures. These effects cannot be predicted or eliminated solely by static analysis, as they depend directly on the dynamic evolution of the heap throughout system execution.

Finally, the need for explicit deallocation via free() transfers

to the application the responsibility of correctly managing the lifetime of

dynamic objects. Errors such as memory leaks, multiple frees, or the use of

invalid pointers introduce incorrect behaviors that are difficult to detect

and reproduce, especially in long-running systems. Taken together, these

factors make dynamic allocation incompatible with the predictability,

analyzability, and reliability requirements demanded by deterministic systems.

3. Experimental Environment

This section describes the experimental environment used to conduct the tests presented in this work, including the hardware platform, the real-time operating system, heap configuration, and the development and debugging tools employed. The goal is to ensure reproducibility and to contextualize the results observed in the subsequent sections.

3.1 Hardware platform

The experiments were conducted on a development board based on the TI AM243x microcontroller, equipped with an ARM Cortex-R5F core. This architecture was chosen for being widely used in industrial and real-time embedded applications, offering deterministic behavior, JTAG debug support, and direct execution from RAM memory.

The Cortex-R5F operates without virtual memory support, using an MPU (Memory Protection Unit) instead of an MMU. It uses direct physical addressing, where the logical address is identical to the physical one. This characteristic allows precise observation of the memory layout and heap evolution throughout system execution, without interference from address translation or paging mechanisms.

3.2 Real-time operating system

The operating system adopted was FreeRTOS, widely used in real-time embedded systems. FreeRTOS provides multiple heap allocator implementations, allowing explicit configuration of the dynamic memory management strategy used by the system.

For the experiments described in this article, the heap_4

implementation was used, which organizes the heap as a linked list of

free blocks, with support for block splitting and coalescence of

adjacent regions when possible.

3.3 Heap configuration

The FreeRTOS heap was statically defined at design time through the

configTOTAL_HEAP_SIZE parameter. The heap region resides

entirely in contiguous RAM memory, with fixed and known boundaries, as

specified in the project linker script.

During the experiments, all dynamic allocations were performed through

the pvPortMalloc() API and released with

vPortFree(). This approach allows direct observation of

the allocator’s internal behavior, including metadata modification,

reorganization of the linked list of free blocks, and the effects of

internal and external fragmentation.

3.4 Development environment and debugging tools

System development and debugging were performed using Code Composer Studio (CCS), version 20.3.0, the official Texas Instruments environment for embedded software development. CCS was used both for compilation and runtime analysis.

Debugging was conducted via a JTAG interface, allowing direct inspection of RAM memory. In particular, the debugger’s memory browser was used to monitor the region corresponding to the FreeRTOS heap during allocation and deallocation calls.

The addresses returned by calls to pvPortMalloc(), the

layout of allocated and free blocks, and the evolution of metadata

implementing the internal heap linked list were directly observed.

These observations were performed without additional instrumentation

that could alter system behavior.

3.5 Considerations and limitations

The experiments presented do not aim to characterize temporal performance or establish execution-time bounds for allocation operations. The focus of the study is exclusively structural, aimed at understanding the internal operation of the heap and the side effects of dynamic memory allocation in real-time systems.

The results should therefore be interpreted as representative of the structural behavior of dynamic allocation in deterministic embedded systems, and not as an evaluation of absolute performance or execution time.

4. Experimental Evaluation

This section describes the experiments conducted on real hardware with the FreeRTOS real-time operating system running on a TI AM243x microcontroller (ARM Cortex-R5F). The objective is to directly observe, through debugging and memory inspection, the internal behavior of the heap and the side effects associated with dynamic memory allocation, as discussed in the theoretical background.

4.1 Experiment 1 — Incremental heap evolution

Objective. To analyze how the heap evolves over successive allocation calls, highlighting the progressive modification of its metadata and the dependence on the allocation history.

Methodology.

Sequential calls to pvPortMalloc() with different sizes were performed,

without intermediate deallocations. After each call, the memory region corresponding

to the heap was inspected using the debugger memory browser, allowing direct

observation of metadata and the internal reorganization of the heap.

4.2 Experiment 2 — Allocation below the minimum size

Objective. To demonstrate the minimum allocation granularity of the heap and the memory waste associated with requests below this limit.

Methodology.

A call to pvPortMalloc() was made requesting a number of bytes smaller

than the minimum size supported by the allocator. The memory layout was inspected

again via debugging after the allocation.

4.3 Experiment 3 — Freeing an intermediate block

Objective. To analyze the effect of freeing an intermediate block on the heap structure and the formation of non-contiguous free regions.

Methodology.

After performing multiple consecutive allocations, an intermediate block was freed

using a call to vPortFree(). The state of the heap was inspected

immediately after the deallocation.

4.4 Experiment 4 — Reuse of a free block and internal fragmentation

Objective. To demonstrate how the allocator reuses previously freed blocks and under which conditions block splitting does not occur.

Methodology.

After freeing a larger block, a new call to pvPortMalloc() was performed

requesting a size smaller than the available free block. The allocator behavior was

analyzed through direct inspection of metadata.

5. Experimental Results and Analysis

5.1 Experiment 1 — Understanding Heap Operation

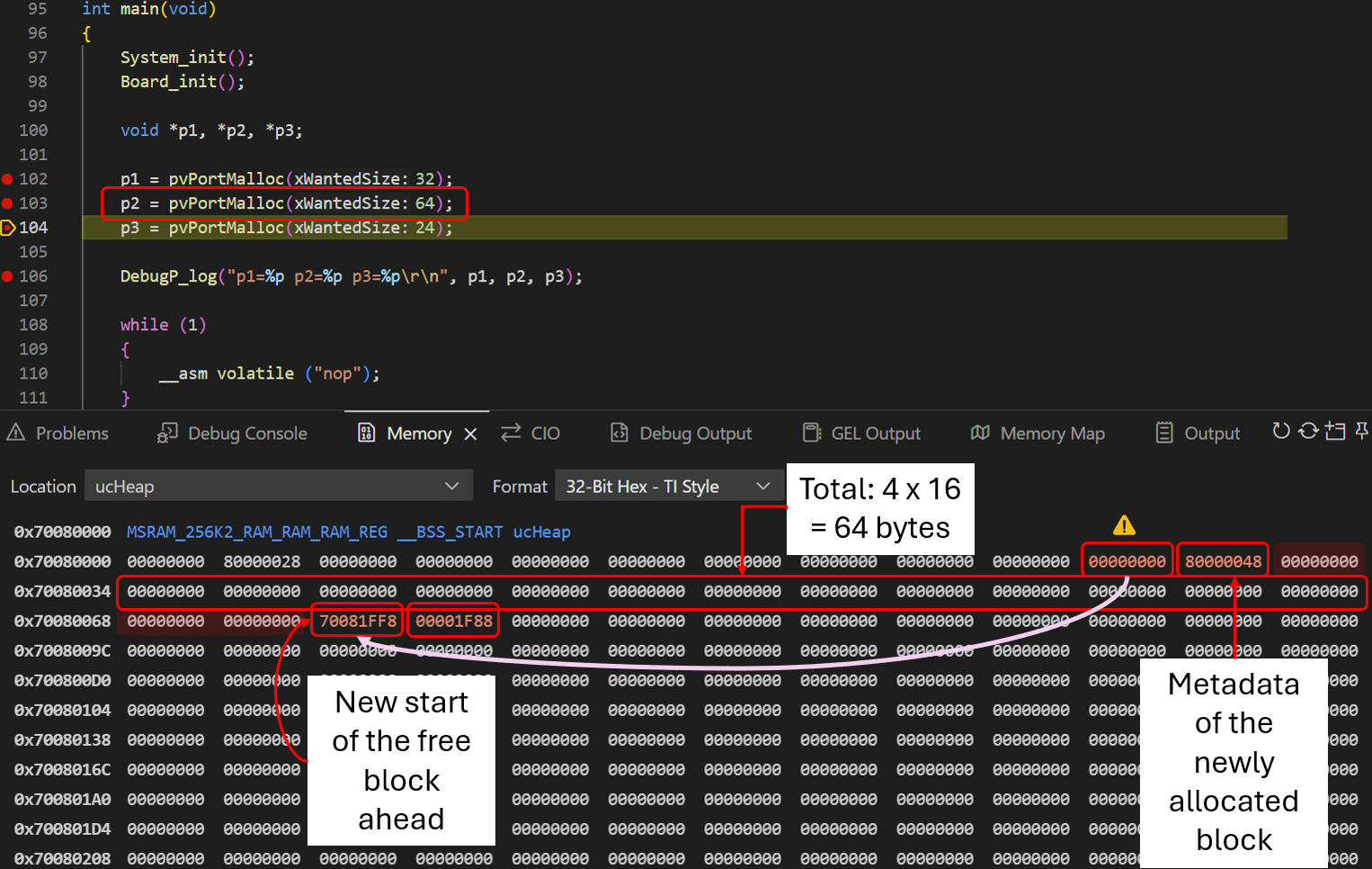

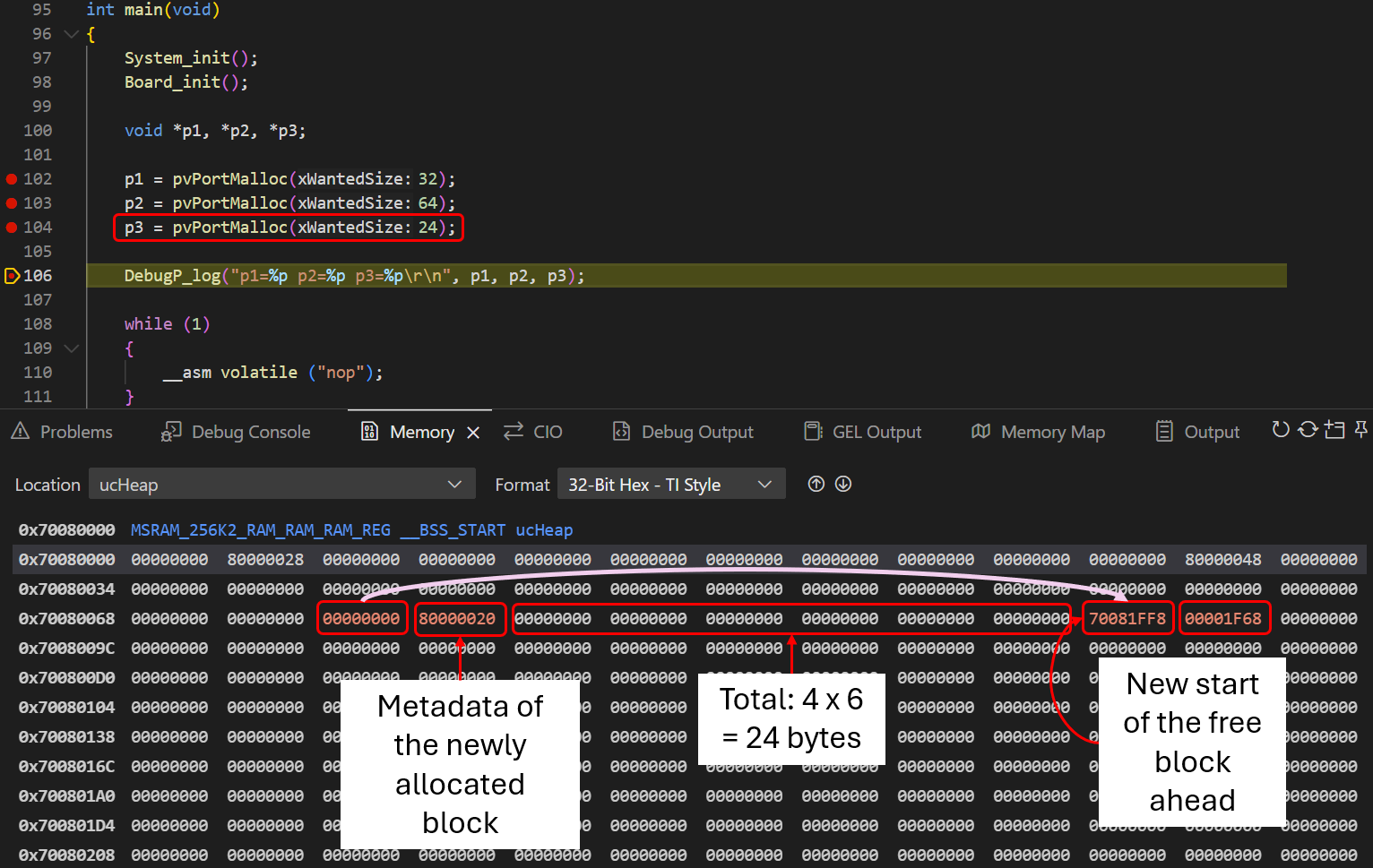

By performing successive calls to pvPortMalloc(), it is observed via debugging

that the heap state evolves continuously. Before the first call, the heap is completely free.

After allocating 32 bytes, a change is observed in the first metadata block (the

BlockLink_t structure). The address returned to the application corresponds to

the beginning of the second block (the payload), and modifications are observed in two

subsequent words that mark the next pxNextFreeBlock and the remaining

xBlockSize.

On the second call, the allocated block is placed immediately after the previous one.

The allocator locates the free space because the heap behaves as a linked list

(linked list). The value marking the beginning of the next free block is moved to

the end of this newly allocated block. An important point observed in the debugger is that

the xBlockSize stored in the metadata is always larger than the requested size,

as it includes the size of BlockLink_t and the portBYTE_ALIGNMENT,

highlighting the presence of metadata.

On the third call, the process repeats: the pointer marking the beginning of the free block advances again. The debugger shows that the heap leaves "empty" memory positions between blocks to maintain alignment for the Cortex-R5 architecture, which already introduces a subtle form of fragmentation and at the same time moves the pointer that marks the beginning of the free block forward.

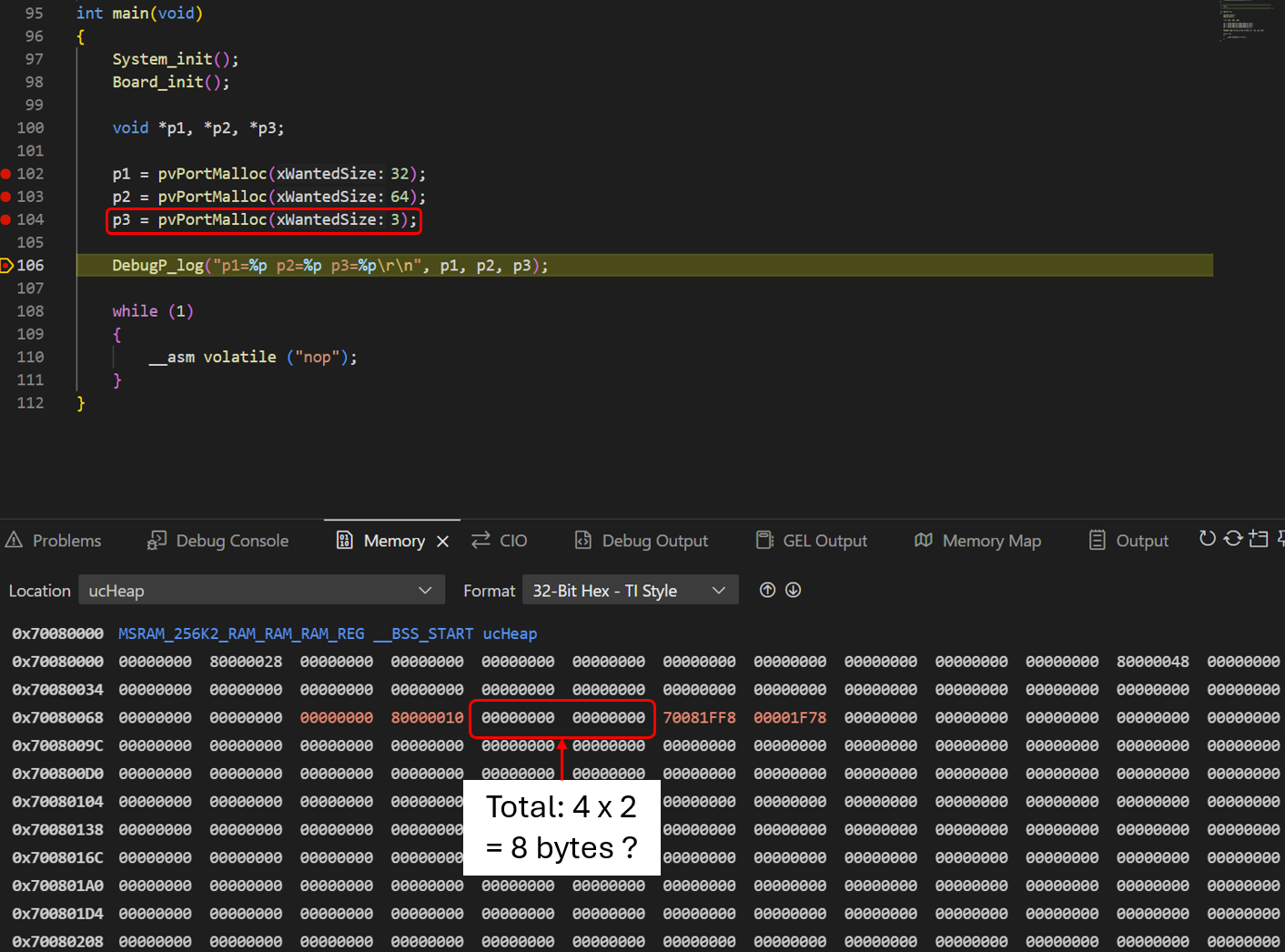

5.1 Experiment 2 — malloc of a value smaller than the minimum

In this experiment, a value below the minimum allowed by heap_4 was requested.

The result was the occupation of 2 words (8 bytes), resulting in immediate waste.

This occurs due to the heapMINIMUM_BLOCK_SIZE macro, which prevents free blocks

from becoming so small that they cannot store their own metadata in the future. This phenomenon is characterized as internal fragmentation: metadata and payload are rounded up to satisfy architectural alignment. Consequently, more memory is reserved than requested, leaving a portion unusable by the application.

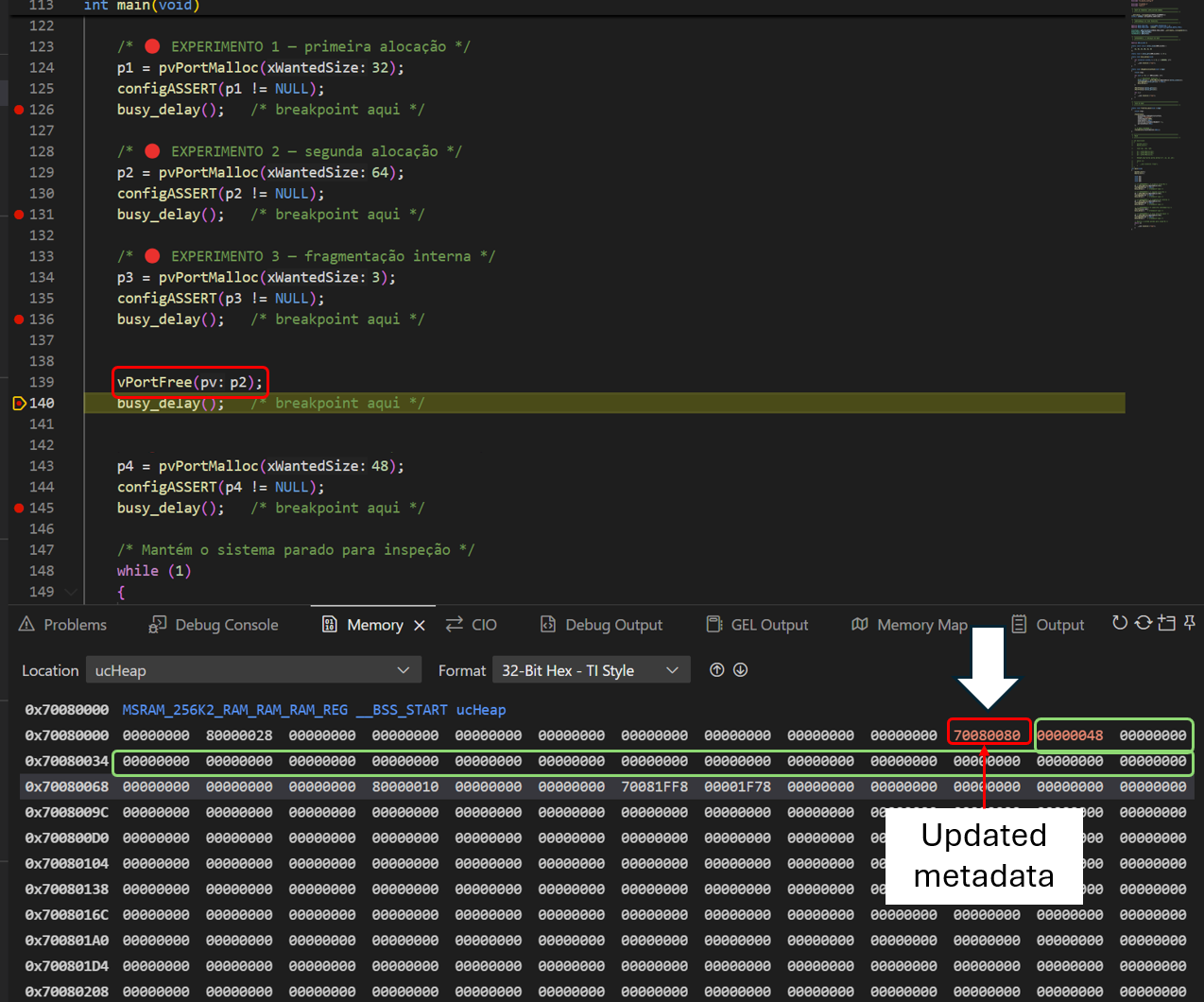

5.1 Experiment 3 — Freeing an intermediate allocated block with free()

When freeing a central block (p2), the allocator executes the function

prvInsertBlockIntoFreeList(). The pxNextFreeBlock field of the

previous block is updated to point to this new free space. In the debugger, it is noted that

there is no data movement; the block simply "re-enters" the linked list. Since the neighboring

blocks are occupied, coalescence does not occur, creating an isolated free

region. This is external fragmentation: the space exists, but is "trapped"

between occupied blocks.

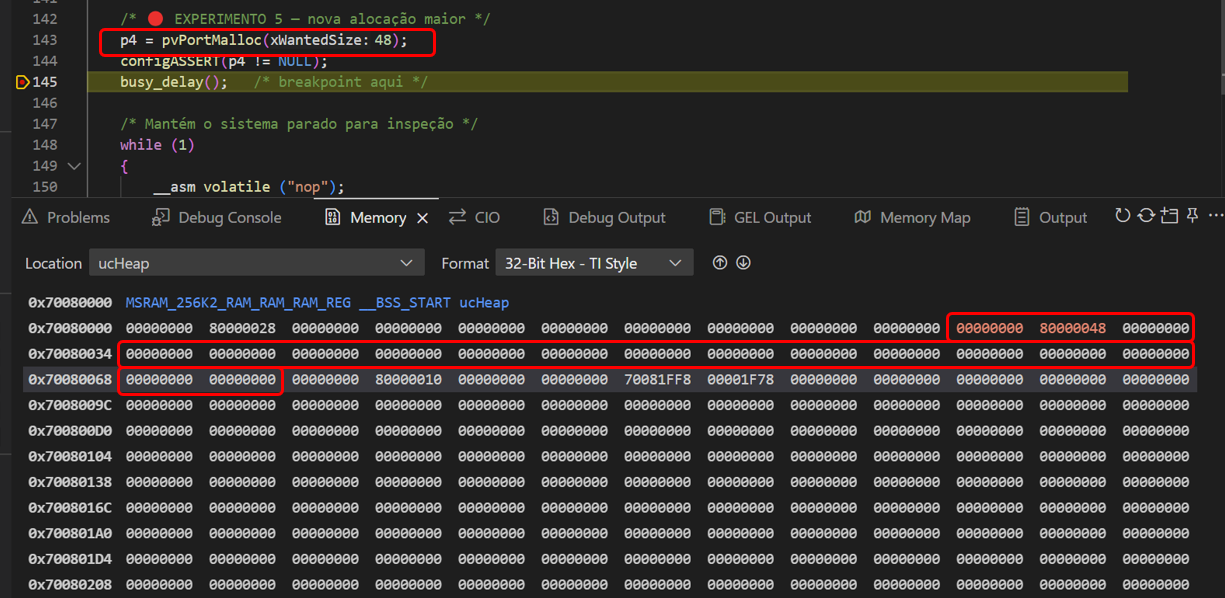

5.1 Experiment 4 — New malloc() requesting 48 bytes

When attempting to allocate 48 bytes, the allocator reused the 64-byte block left by p2.

Although there was a remaining "slack" of 16 bytes, heap_4.c decided not to split

the block (splitting). This happens because the remaining space would be less than or

equal to heapMINIMUM_BLOCK_SIZE, which would make it impossible to create a valid

linked list node in that region. The entire block was delivered to the application, generating

another case of internal fragmentation and demonstrating how the heap layout becomes highly dependent on execution history, compromising spatial predictability.

6. Conclusion

The experiments conducted on real hardware validated that the FreeRTOS heap_4

implementation prioritizes efficiency and low overhead through a linked list of free blocks;

however, there is still a significant amount of overhead between successive operations.

Direct memory inspection revealed that 8-byte alignment and the BlockLink_t

structure impose RAM consumption greater than requested, resulting in

internal fragmentation inherent to the allocator design.

The practical analysis of vPortFree() and subsequent allocations demonstrated

that external fragmentation and the absence of splitting for small blocks

make the memory layout highly dependent on execution history. This behavior confirms that

heap_4 does not provide strict guarantees of spatial and temporal predictability.

In summary, this study reinforces that, although robust, the use of dynamic allocation in critical real-time systems requires caution. The observed indeterminism justifies the preference for static allocation or memory pools in certified projects, where the variability introduced by fragmentation represents a risk to system determinism.

Code Availability

The source code for the experiment is available on GitHub:

Comentários e discussões